Posted: Tuesday, March 04, 2008 8:35 PM by Alan Boyle

Microsoft via AFP - Getty Images Microsoft via AFP - Getty Images |

Microsoft's LucidTouch displays "pseudo-transparent"

fingers on a handheld computer screen. Sensors

keep track of your fingers on the back of the device.

|

Once a year, Microsoft Research gives

outsiders a glimpse of its high-tech frontiers: gizmos that transform

your fingers into ghostly digits on the screen, or make you look like a

Webcam celebrity ... viewers that let you unravel the inner workings of

the cell, or explore the outer depths of the cosmos ... sensor networks

that monitor how climate change affects glaciers in the Swiss Alps, or

how the chemistry of life works at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

Even though I work right on Microsoft's main

campus, I'm usually counted as one of those outsiders - but today, I

finally got my first glimpse at TechFest, a science fair geared for grown-ups.

Microsoft Research TechFest has been around for seven years, but

until last year it was meant exclusively for the software company's

employees. It's actually a cross between a science fair and a trade

fair, with researchers showing their innovations to product developers

who might actually use them.

Last year, the company opened up the TechFest displays for one day

to potential customers and partners, as well as journalists and

dignitaries. The same system was in effect this year.

Microsoft may be a partner (along with NBC Universal) in

the msnbc.com joint venture, but we're treated pretty much like other

journalists when it comes to press access. So, armed with my press

pass, I walked over to Building 33 on the Redmond campus this morning,

waltzed in the door and blended in with the crowd - which included

representatives from NASA, the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research

Projects Agency and a host of universities.

Clearer view of virtual telescope

The headliner at the event was the WorldWide Telescope, an astronomy program that we first wrote about last week (when it was demonstrated at the TED conference).

Today, researchers at Microsoft and beyond were more willing

to talk up-front about the virtual telescope, which is expected to

go into free public release late this spring.

Like Google Sky, Stellarium

and other such programs, WorldWide Telescope blends astronomical

imagery from multiple sources using a clickable, zoomable interface

that simulates the night sky on your desktop. Microsoft Research's

Curtis Wong said he hoped the program would make its mark by letting

astronomers and the general public create their own virtual tours of

cosmic wonders.

"If you can create a PowerPoint presentation, you can create a guided tour of the sky," Wong told me.

One of the presentations demonstrated today was created by

a 6-year-old Toronto boy named Benjamin, who gave a charming tour of

the Ring Nebula. "My dream for this is to have more and more of these

stories," Wong said.

But the WorldWide Telescope is more than a child's plaything:

Professional astronomers are already planning to use it to archive

data, present their observations in an academic setting, and even open

the way for analysis and discovery.

"The astronomy community is really excited about it, mainly because

we paid attention to a lot of details they care about," Wong said.

One of the early adopters is Alyssa Goodman of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

"What we're doing is adding the functionality that only

professionals would care about," she told me in a phone interview.

"Making tours of papers, for example, or being able to do things with

the coordinate system. ... The important thing is that it will become

probably the premier interface for the professional virtual

observatory."

The other sky software packages have their pluses as well, she said

- and competition is usually a good thing for everyone involved.

"The way I see this is, it's almost like the browser wars," Goodman

said. "The content is already out there, and right now I see this as a

browser for the sky. ... The dream of the whole virtual observatory

community is that all of these tools will interoperate as well as the

Web does."

The technology behind the WorldWide Telescope could spawn other products as well.

"Some of the things we're able to do there may be brought into the

medical sphere," Craig Mundie, Microsoft's chief research and

strategy officer, said at TechFest. He pointed out that once you have

the mechanism for blending terabytes of data from multiple

sources, you could use that mechanism to present astronomical

imagery from radar scans and X-ray telescopes ... or medical

imagery from PET scans and hospital X-rays.

The WorldWide Telescope wasn't the only virtual realm on display. Here's a quick rundown on some of TechFest's other wares:

Virtual fingers

The coolest gizmo I saw was a handheld mobile device tricked out with a technology called LucidTouch, which allows you to work a touchscreen by moving your fingers on the back

of the device. A ghostly, semitransparent projection of your fingers

appears on the screen itself, thanks to a Webcam and a touch-sensitive

surface on the back side.

Alan Boyle / msnbc.com |

Microsoft Research's Patrick Baudisch demonstrates

the LucidTouch device at TechFest.

|

Microsoft Research's Patrick Baudisch

developed the technology to do away with the frustration of having to

put your big fat fingers on a small touchscreen. The

"pseudo-transparent" fingers are overlaid on touchscreen controls and

give you an eerily effective sense of feedback as you twiddle your

phantom digits.

Eventually, Baudisch hopes to do away with the

clunky Webcam sticking out from the back of the device and get the

technology built into a wide range of small-screen devices, ranging

from smartphone-style wristwatches to handheld game consoles.

"Using the same surface twice isn't a great idea," Baudisch

explained. "So why don't we use the surface that hasn't been used: the

back."

Virtual cells

Andrew Phillips and his colleagues

at Microsoft Research's British facility have developed a visual

programming language, known as the Stochastic Pi Machine

or SPiM, to help biology researchers analyze how cells do their work.

The program can take a tangled chemical pathway and figure out what

quantities of which proteins should be produced by that pathway.

Microsoft Research / msnbc.com |

Click for video: Msnbc.com's Alan Boyle narrates

animations from Microsoft Research that represent

cellular signaling pathways at work.

|

"We want to build a model of a biological

system on a computer," Phillips said. "We take a very complicated

network and break it up into more manageable parts."

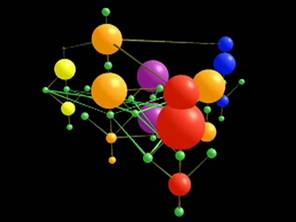

Graphic representations of

chemical reactions in the cell show proteins as colored balls of

various sizes, growing and shrinking as they are built up and broken

down. The green connecting lines represent signaling pathways.

Researchers can compare the predicted outcome

of a biological process with the actual results of their experiment, to

find out if their model for the process is correct. Someday, the

simulations might even suggest new strategies for

countering cancer or developing new drugs.

Sensors on the ocean floor

Microsoft is

participating along with the University of Washington and the Monterey

Bay Aquarium in a program called Trident, which is developing a sensor

system for studying the Pacific Ocean's active

seafloor. Trident meshes with wider efforts known

as Project Neptune and the Ocean Observatories Initiative.

Eventually, scientists could be watching the ocean floor

remotely with HDTV cameras, seismometers, sonar and other scientific

instruments - with all the data flowing back to land via a fiber-optic

network.

"Once you have thousands of sensors, how do you process all that

data?" said University of Washington oceanographer Deborah Kelley,

a member of the Neptune team.

That's where Microsoft is helping out, by devising the data

flow management system that will let researchers hundreds of miles from

shore interact in real time with their experiments. "It

democratizes science," Microsoft Research's Roger Barga explained.

Sensors on mountaintops

Another sensor-based scientific project is called SenseWeb. Swiss researchers are using SenseWeb to knit together data from weather monitoring stations planted in Switzerland's Genepi rocky glacier.

A software program called SensorMap can extrapolate from the

individual wind and temperature readings to develop time-lapse maps of

the entire area. SensorMap also could be used to keep track of

Seattle-area traffic or San Francisco airport parking, as shown on the project Web site.

Lights, Webcam, action!

One of the

not-yet-ready-for-prime-time technologies we saw demonstrated was a

little something called "Active Lighting." It's basically two

low-power LED arrays that are set up on each side of a Webcam-equipped

computer monitor. When you turn on the video, a computer

program checks your image and starts switching different-colored

lights on and off.

"It analyzes the video and adjusts the lighting so it looks nice," Microsoft Research's Zhengyou Zhang explained.

How does the computer know when your image looks the nicest? Zhang

said the software compares the lighting on your face against a database

of celebrity photos. The more you look like a celebrity, the better the

lighting must be. And who can argue with that?

For more about TechFest, check out these reports from CNet, Computerworld, Gizmodo, InfoWorld, Wired and Microsoft's TechFest Live blog.